Art and Craft Instruction at the Bethlehem Female Seminary, 1742-1869

by Roy Winkelman

This article is adapted from chapter 9 (pp. 299-324) of my doctoral dissertation, Art education in the non-public schools of Pennsylvania, 1720-1870. Having covered various types of art instruction in private schools prior to 1870 in previous chapters, I turned my attention to one particular girls’ school as a case study. As I explained earlier in the dissertation, the word “seminary” was generally used to describe a private schools for girls, whereas the term “academy” was usually used to identify the parallel institution for boys. The Bethlehem Female Seminary was founded in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in 1742. This school was one of the oldest and best-known girls’ boarding schools in America and served as a model for many schools which followed it. The school continues to this day as Moravian Academy, having merged with Moravian Preparatory School in 1971.

At this time, the images are scans of photocopied illustrations from my printed dissertation. I hope to locate my original photographs of the artifacts this summer and replace the poor quality images in the current document.

Page Contents:

The Early Years

Opening to Non-Moravians

Into the Nineteenth Century

The Arrival of Grunewald

The Early Years

The Bethlehem Female Seminary traces its origin to a Moravian school founded by the sixteen-year-old Countess Benigna, daughter of Nicholaus Ludwig, Count von Zinzendorf. The Moravians are a Protestant sect which banded together as the Unitas Fratrum in Moravia in 1457. In 1722, after years of persecution, Count Zinzendorf offered them asylum on his baronial estate, Herrnhut. Seeking religious freedom and missionary opportunity, many members migrated to America, arriving in Bethlehem in 1740.

The Moravians deplored the undeveloped state of education in Pennsylvania, and so on May 4, 1742, Countess Benigna opened a boarding school for girls in Germantown. During the following seven years, the school was moved frequently among several Moravian settlements, finally finding a home in Bethlehem.

From 1742 to 1785, the school was open only to Moravians, and few records survive. A diary notes that the November 1756 exams concluded with musical selections and a display of “samples of the pupil’s penmanship, drawing, spinning, knitting and needlework.” [1]

In the Moravian community, the students were regularly exposed to works of art. Count Zinzendorf’s personal secretary and artist, Johann Jakob Mueller, had accompanied Zinzendorf on his first visit to Pennsylvania in 1741 and stayed two years. A painting of Mueller’s was placed in the chapel in 1741. Then in 1754, the European-trained painter, John Valentine Haidt, was called to Bethlehem as official church painter. Haidt produced many paintings for both educational and religious purposes. The Moravian Sisters, from whom the teachers for the school were selected, were also known for their artistic talents, particularly needlework and ornamental penmanship. They produced an embroidered banner which was presented to General Pulaski in 1778.

During the Revolution, Bethlehem often found itself in the middle of the war effort. Twice, Bethlehem provided shelter for the national military hospital, and nearly every political leader passed through the town at one time or another. Many of the Congressional Delegates and military officers took time to inspect the whole community and were especially impressed with the quality of Moravian education. After peace returned to the land, many of these leaders, who did not happen to be Moravians themselves, sought to place their daughters at the Bethlehem School.

Opening to Non-Moravians

In 1784, the Countess Benigna and her husband, Moravian Bishop John de Waterville, returned to Bethlehem to take part in the deliberations regarding the future of the school. It was decided to reorganize the school in 1785 to admit non-Moravians, the first such student arriving in May of the following year. From this time on, many records of the school were preserved and provide a rich source of information regarding the practice of art education from 1785 to 1870.

The first principal of the reorganized Seminary was John Andrew Huebener. During his five-year tenure, we find many examples of ornamental needlework, drawing, and painting instruction. Huebener’s notice concerning the policies of the new school stated that ‘for private tutoring in music and drawing, whenever such is requested, a separate charge will have to be made to the parents and guardians, for which a bill will be sent to them quarterly.” [2]

A typical student schedule of this period included:

8:00 Cyphering School

9:00 German Reading School

10:00 Children’s Devotional Service

11:45-1:00 Lunch and Leisure

1:00 History School

2:00 Geography School

3:00 Tambour and Music

4:00 Drawing and Painting. [3]

Saturday mornings were also frequently given to needlework. [4] In the evenings, the students would gather around their tutoresses for conversation or to listen to readings. During this time, the students would also be working on their needlework or spinning.

In 1787, the additional fee for tambour work and drawing was 17s 6d per quarter. The two needlework teachers at that time were Ann Marshal (manager of the Single Sisters’ house) and Maria Rosina Schulze. One entry in the 1787 ledger notes that Schulze was paid 12s for teaching four students for twelve weeks. The fees collected from the four students totaled 3£ 10s. Painting was also taught from the earliest days of the reorganized Seminary, as indicated by a diary entry from 1788 recording that “Sister Kleist kept our first painting-school, with eight of the children.” [5]

Christmas at the Seminary was a special occasion shared with the townspeople. The Sisters created a nativity scene of “summer landscapes, with mossy banks and mimic lakes and streams.” [6] Rooms were decorated with evergreens, and transparencies of nativity scenes were displayed for the students. The older students prepared ornaments and flowers for Christmas decorations. [7]

On the second day of the May 1789 examinations, drawing specimens were passed among the invited guests for inspection. [8] At this same public examination a dramatic piece written by Sister Kleist (who kept the “painting-school”) was presented. Excerpts referring to the arts follow:

MARIA COX.

The useful arts, and all their first invention,

Were for our good,—God’s own, His prime intention.

MARIA COX.

The art of drawing I admire,

When clothed in red and green attire.

And even the pale, blushing lines

My pencil first to paint designs,

I like to see, and know to prize them well,

Aa they in tambour and embroidery tell

My needle how to mend her pace

In straight and curved lines, and in flowery ways.

Thus, without drawing, would my needle glide,

And tambour and embroidery lead aside.

HANNAH LANGDON.

Needle, and especially tambour work,

are my dearest and most agreeable employments.

MARY UNGER.

Knitting, sewing, and spinning are not only very useful acquirements,

but also indispensably necessary to our sex. [9]

In another dramatic piece, “Rural Life” by Sister Langaard, spinning, sewing, and knitting are seen as a form of godliness. In this excerpt Clementia, a visitor from the city, asks the three “industrious” women about their work.

Clementia. Please inform us, do you mean it in reality an honor for persons of your rank and estate to meddle in all outward affairs and take your work in your own hands?

Industria. Surely it is a greater honor to any person, were she even a princess, to make use of her own hands, as given her by her Creator to some good purpose, than keep them idle.

Prudentia. Had we not the Holy Scriptures to instruct us in this point, we see all nature busy around us, and if we, as human beings that are of the noblest construction, should waste the gifts bestowed on us, by idleness, surely He, as a righteous God, would require a severe account of us.

Laurella. Of this the Holy Scriptures inform us, and show us, in the lives of the blessed patriarchs, how they increased in piety of heart the talents bestowed on them by God, in working with their own hands, although they had many servants. But, above all, God’s own Son, our Saviour did not abhor to do hard labor, but followed Joseph’s trade. [10]

In another section of the same work, the four daughters of Evelina are also found to be industrious.

Prudentia. Do the little misses find pleasure in industry?

Children, [courtsying and smiling]. Yes ma’am.

Evelina. They learn to knit, spin, sew, tambour, embroider, draw, and all a lady ought to learn; and I must say, to their credit, it is a pleasure to them.

Children. I thank you, ma’am. [11]

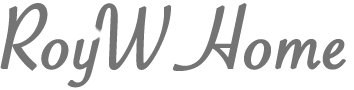

Fall, 1789, diary entries show the students “busy in painting and working tambour and embroidery to have in readiness by the examination.” The fall quarter exam was held on October 10; and, as was the custom. the students’ writing-books, drawings, and paintings were shown to the guests after demonstrations of English, German, ciphering, and so forth. [12] Figures 1 and 2 may have been displayed at this examination.

Figure 1. Antique Figures, Jane Byvanck, 1789, Pencil drawing at age 11 (8.5″ x 7.25″) Moravian Archives.

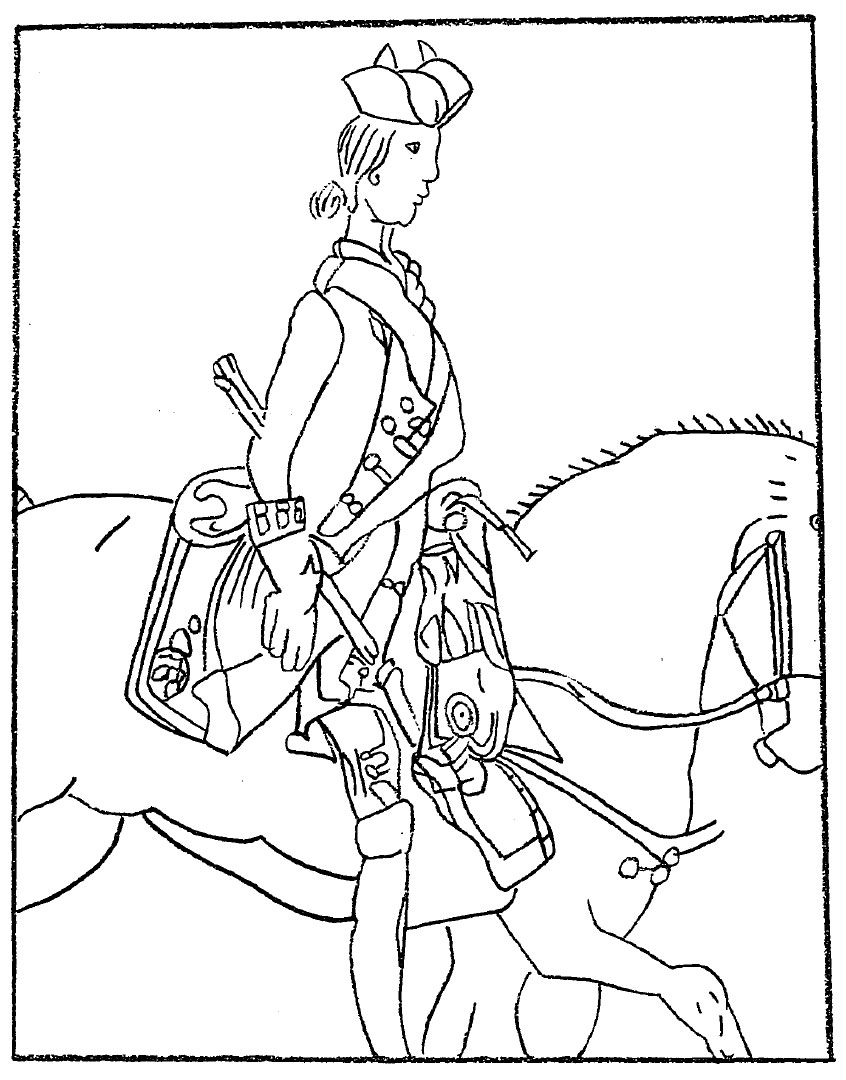

In 1790, Jacob Van Vleck became principal of the Seminary and the cornerstone for a new Seminary building was laid. (See figure 3.) Under Van Vleck’s direction, art and music were encouraged. Standard works on art and science were added to the library. [13] Patterns for needlework and drawing were acquired, and filigree-work was also added to the growing list of subjects offered. Van Vleck also emphasized the art of penmanship, sometimes appointing three or four hours a day for this study. He took personal interest in this matter, requiring in 1791 that “on the first Monday of every month after Writing School one Miss of each room, be appointed for the purpose, carry the Writing books to the principal’s Room, and fetch them back the next morning.” [14] Proficiency in writing was a pre-requisite for drawing and painting instruction. [15]

Figure 3. View of the Bethlehem Female Seminary, 1790.

Reichel and Bigler, Moravian Seminary Souvenir, p. 105.

In 1790 the annual tuition of £20 (Pennsylvania currency) included plain sewing and knitting. “For instruction in fine needlework; including drawing, also two guineas per year.” [16] A student taking filigree in 1794 was charged:

| s | d | |||

| Charge for learning Philegry | 15 | – | ||

| Philegry Needle | 3 | 9 | ||

| Gum, paper, pasteboard and Riband | 3 | 9 | [17] |

The spring exams in 1791 included “specimens of our writing, drawing, painting, embroidery, and tambour, and of the younger misses’ knitting and samplers.” [18] The watercolor reproduced as Figure 5.1 and the two drawings reproduced as Figures 4.6 and 4.19 may have been shown at this exam or perhaps at the fall exam of the same year. Visitors to the Seminary at any season would also be shown samples of student art. A correspondent to the June, 1791, Massachusetts Magazine wrote “we passed through several divisions of the school. We examined the tambour and embroidery and never did I see anything in that line equal to it. We attended to their composition and painting, and I was inexpressibly charmed.” [19]

Needlework began to display the growing interest in mourning subjects. One student, intent to produce a fashionable fire screen, wrote to her sister. “It will be no trouble for me to work you a screen. I shall do it with the utmost pleasure; I think it will look best on white sattin…. But I wish you to chuse a Motto to go in the Urn. If you wish a name let me know and I will do it.” [20] As interest in mourning art increased (particularly after the death of Washington), the Seminary acquired such texts as:

Mineralogy, Miscellany, Monograms, Music which contained instructions on how to draw drapery on a figure and how to draw shadows; a book on Roman statues, which supplied designs for drawing mourners; a German Encyclopedia of Arts and Sciences, which illustrated ways to draw plinths and a Book of Landscapes, Outlines, and Shadows proper for Learners to draw after. [21]

Paintings were also made as presents commemorating birthdays, friendship, or special visits of friends or family. The March 28, 1791, entry in the Girl’s School Diary notes that, “Today was our dear Sister VanVleck’s birthday. Several of the Misses with Sister Kleist and Sister A. J. Levering went about half after 5 and sung her several verses, presented her likewise with a piece of painting framed.” By 1799, Benedict Bernade, a local painter, was supplementing his income by providing wooden panels for the students to paint on. For one two-week supply, he received the considerable sum of 9£ 13s 6d. [22]

Class recitations at the Seminary also included information on the types and orders of architecture, the elements and types of painting, and several contemporary sculptors. A student’s notes on these subjects from 1791 are reproduced as Appendix D.

Into the Nineteenth Century

From 1800 to 1813, the principal of the Seminary was Andrew Benade, father of the landscape painter James Arthur Benade. During his tenure, artificial flowers became a popular craft item with the students. “Day Book C: 1794-1803” shows charges of 1£ 2s 6d made to many students beginning in 1802. By 1808, artificial (cloth) flowers showed an income of $103.36 compared to income of $353.90 for drawing and needlework. [23] Four years later, income from drawing and needlework had increased about 105, but artificial flowers had nearly quadrupled.[24] Students pursuing artificial flowers frequently purchased cotton, cambric, muslin, sewing silk, starch, wire, ribbon, stands, and gum arabic from the school store. [25]

Figure 4. Moss Painting, 1808 or 1809. “First House of Bethlehem” done by the roommate of Marie Eyre Ashbrumer at Lititz. Courtesy of the Moravian Museum of Bethlehem.

During this time, students continued to paint on paper and also on the wood panels that Bernade was still supplying. There was steady interest in tambour and drawing. Some students made dried moss dioramas such as the one illustrated above in figure 4. And the 1801 examination (Appendix E) shows content very similar to the 1797 class notes. Afternoons were still reserved for art and music as evidenced by the following regulation from 1801:

During the hours appointed for the Sewing School, Knitting, etc. from 1 to 4 o’clock, the Misses will carefully avoid all unnecessary talk or running in and out of the room at random, as it would greatly disturb those that have their Music School or practice on the Instrument. [26]

Maria Schulze continued to teach needlework and was joined by Ann Green, Joana M. Weber, and Mary Allen, who had been a student at the Seminary from 1789 to 1799. Mary Salmae Meinung taught drawing and painting and was joined by Charlotte Fischer in 1813. Green and Weber together were paid $62.16 in 1809. From 1809 to 1812, Meinung’s annual income from art instruction increased from $ll.36 to $19.28 1/2. [27]

The War of 1812 and three school administrations in as many years had taken its toll on the Seminary when Henry Steinhauer arrived from England in 1816 to assume the principalship. Under Steinhauer, painting in ebony and fancy-work in pasteboard were introduced. The December, 1816, inventory includes a few sheets of ivory, suggesting that miniature painting on ivory was also practiced. The inventory the following year lists velvet, velvet paints, and velvet brushes indicating the introduction of a branch of painting that was to reach the peak of its popularity about 1820, and then slowly decline during the next decade.

Steinhauer was elected to membership in the American Philosophical Society and made many friends for the Seminary in influential circles. He began the custom of “social evenings” for the older students in his Principal’s room. “He…invited distinguished scientists and artists from Philadelphia to share the pleasures of these evenings, and presented them to his pupils, so giving his soiree the atmosphere and manners of a drawing room.” [28] At other times, a book would be read aloud as the students busied themselves with various ornamental projects “such as paper screens and note-holders.” [29] Steinhauer also taught drawing himself.

Charles Seidel served as principal from 1818 to 1819 and from 1822 to 1836. In 1818, several examples of needlework flowers in crepe and ribbon were brought from Germany by visitors to the Seminary. The pieces received so much admiration that Seidel had several of the tutoresses trained in the art. Chief among them was Polly Plum. Under her instruction, this became a popular form of needlework through the 1830s. Figure 5 is an example of ribbonwork by a Seminary student.

Figure 5. Ribbonwork, Caroline Kummer, 1830. Courtesy of the Moravian Museum of Bethlehem.

Harriet Gould Drake Tinkam recalled her afternoons at the Seminary as a student in 1817:

One afternoon of the week was devoted to drawing, another velvet painting and music, another to worsted work and music, writing, reading end spelling, one afternoon, and one afternoon we sat in our sittingroom and were taught darning stockings with as much care as we were taught embroidery. [30]

A very elaborate piece of ribbonwork was produced by the students under Blum’s direction and was presented to Mrs. John Quincy Adams in 1826. The First Lady responded with the following letter:

TO THE YOUNG LADIES OF BETHLEHEM SEMINARY.

The extreme ill health under which I have labored ever since my return to Washington has prevented the earlier acknowledgment of the receipt of the elegant specimen of workmanship so beautifully executed by the pupils of the Bethlehem Seminary and presented to min so very flattering a manner.

The great interest I must ever take in the exertions of my sex to attain to excellence and perfection in the cultivation of their minds and in the acquirement of useful and elegant accomplishments may perhaps entitle me to express my admiration of the work with which you have honored me, in which the purest taste and neatest execution are conspicuous, and return my grateful thanks for the honor thus conferred on me by the distinction so bestowed,—a sense of which is deeply impressed on my heart.

With assurances of the highest respect, permit me to offer to the young ladies of the Bethlehem Seminary the best wishes for their happiness and prosperity.

Louisa Catherine Adams [31]

Interest in ribbonwork resulted in a fast decline in the number of students taking lessons in tambour. Tambour School revenue peaked at $610.97 in 1814; by 1822, it plummeted to $9.93 which indicates a drop from about 50 students to about one student.

Theoremplates were purchased in 1823 for velvet painting, and something called “spunge painting” made a brief appearance in 1830 and 1831. Ebony painting continued in popularity, with students making projects such as shaving boxes, work boxes, and writing desks. The fee for ebony painting was usually $2-3.00 per quarter with additional charges for materials. Beadwork and lacework both showed small revenues for the years 1825 to 1830. Waxwork was also introduced.

One fascinating receipt reveals the amount of time that a ribbonwork proJect could consume, gives the hourly wage of a teacher, and raises a few interesting questions:

Rev Mr. Seidel Dr

To Sophia Krause

For working at Miss Emily Pullen’s Ribbonwork, 60 hours at 4 cts per hour.60 hours

4 cts

$2,40ctsBethm Novbr 1827

Emily had been admitted to the Seminary in 1826, but there is no indication of why an instructor was paid to work so many hours on her ribbonwork. I examined all of the papers in both boxes of needlework accounts from the Seminary and found nothing similar to this.

During Seidel’s administration, Charlotte Fisher continued to teach drawing. Elizabeth and Louis Souter began teaching drawing in 1826 and 1833 respectively. Caroline Bleck taught drawing, velvet painting, and ebonywork. Caroline Siewers taught ebony painting, velvet painting, and worsted work. She was paid 6 cents per hour in 1826. Sarah Horsfield, Polly Blum, Esther Berg, and Sophia Krause taught needlework. Krause received $1.72 in 1829 for working “43 hours at the piece which was exhibited in the Franklin Institute.” [32] Maria Kummer taught worsted work. Her letters commenting on patterns, the difficulty of obtaining baskets for worsted work, and the decline of interest in velvet painting in the late 1820s are recorded in Appendix H.

The Arrival of Grunewald

The painter Gustavus Grunewald came to Bethlehem in 1831. Some of his paintings were installed at the Seminary and others displayed at special occasions, such as Christmas or music festivals. In 1836, John Kummer became Principal of the Seminary, and Grunewald was hired as Drawingmaster.

Grunewald was a graduate of the Art School of Dusseldorf where he learned to paint landscapes of the Rhine valley. He served in the Prussian army, and came to know King Frederick William III of Prussia well. Grunewald was, on occasion, called to Berlin to advise the King on acquisitions for the royal art gallery. He was also offered, but declined, a court appointment.

As Drawingmaster at Bethlehem, Grunewald continued to paint landscapes, now of the Lehigh and Delaware River valleys, rather than of the Rhine. [33] He is often associated with the Hudson River School of painters. It was his practice first to sketch in pencil, add ink, and then watercolor. Later, he would paint in oil from the sketch.

Figure 6. View of the Lehigh River, near Bethlehem. Reichel and Bigler, Moravian Seminary Souvenir. p. 121.

Grunewald took his students outside to paint, often along the tow path of the canal. (See figure 6.) Grunewald, sporting a bushy white beard and broad rimmed black hat, walked with a distinctly military carriage as he led his troop of girls carrying easels and paints. [34] Upon arrival at the chosen location, he would select one particular view and require all of the students to paint the same view while he painted it himself. [35] When teaching in the studio, Grunewald also used his own work as an example for the students. In 1844, the Seminary purchased a “number of patterns in oil and crayon by Grunewald, in themselves a little gallery of artistic gems.” [36] A landscape drawing by Grunewald is reproduced as figure 7.

Figure 7. Pencil Drawing, Gustavus Grunewald. (7.75″ x 10;5″) Moravian Archives.

In 1837, there were about 118 students at the Seminary. In August of that year, four drawing classes were scheduled, each meeting for two hours per week:

| I Monday 11-12:00 | Wednesday 10-11:00 | 12 students |

| II Tuesday 11-12:00 | Wednesday 11-12:00 | 12 students |

| III Wednesday 2-3:00 | Thursday 11-12:00 | 12 students |

| IV Wednesday 1-2:00 | Friday 11-12:00 | 11 students. |

Ribbonwork had two sections, one meeting on Monday and Thursday, the other on Tuesday and Friday, each with six students. The two sections of worsted work met the same days as ribbonwork, and each had 17 students. Ebonywork had 12 students enrolled in October, but by November, seven more had been added. The class was then split into two sections: Thursday 1-3:00 with nine students, and Saturday 1-3:00 with ten students. Assuming a steady school population of 118, we can calculate the following percentages of the student body electing each type of art instruction:

| Drawing | 40% | |

| Ribbonwork | 10% | |

| Worsted work | 29% | |

| Ebonywork | 16% |

Students were evidently permitted to elect more than one art class since several names appear on class lists for different subjects. [37] There was also a drawing class for boys on Wednesday afternoons from 2:00 to 4:00. [38] Grunewald also taught “evening classes, composed of the younger mechanics and apprentices, who were grounded in hard line freehand drawing.” [39]

An interesting list of student evaluations by Grunewald has been preserved from about the year 1859. Some of the more legible entries follow, with original spelling preserved:

slow, but most excelent, much promising

very much promising, excelent

(drawing) improved (ptg) will do

could be better, cariles

very good much promising

beginning to improve

will be a splended drawer excellent

good for the time

has improved very much

very good, but not much attention

industry and very good

(drawing) excelent (ptg) to tiny but good

great progress

slow, but good

gives satisfaction

very slow

will be a splended drawer—most the best. [40]

Oil painting was first taught in 1845 to a class of seven students meeting Saturdays from 1:00 to 5:00. The oil painting classes were kept small. The 1861 Seminary catalogue lists “Oil Painting (in very small classes) for every 3 hours $1.00.”

In the needlework department, there was a steady demand for instruction in worsted work from the 1830s through the 1860s. In 1841, nearly half of the students were taking worsted work. At the same time, ribbonwork was declining in popularity. I have found no record of a ribbonwork fee being charged after 1847.

During Grunewald’s term as Drawingmaster, the other art teachers at the Seminary included: Eleanor Siebert (drawing and painting), Sarah Eberman (drawing), Frances Eggert (drawing), Mary Coffer (needlework), Mary Trombull (needlework), A. Benigna Smyth (worsted work), Mrs. B. Frick (wax flowers and fruit), Caroline Bleck (drawing, velvet painting, and ebonywork), and one of Grunewald’s former students, Rueben Luckenbach, who was hired to teach drawing and painting in 1865. By that year, the Seminary had reached a record 318 pupils, and half of all the admissions applications had to be declined for lack of space. [41]

In 1866, Grunewald resigned his position as Drawingmaster, and Luckenbach was appointed to take his place. Luckenbach had not only been Grunewald’s drawing pupil, but Grunewald had also taught him to paint furniture when he was overwhelmed with orders for his own work. Luckenbach became so interested in painting that he gave up his work as a cabinetmaker to paint. [42] In addition to his position at the Seminary, Luckenbach taught drawing at the Theological Seminary [43] and also a private class of boys at his studio. [44]

The Bethlehem Female Seminary may have been atypical in its longevity, but the types of art instruction it offered were echoed by many private institutions before 1870. When Fannie C. Jones of Richmond, Virginia, entered the Seminary in December of 1869, she became the 5,479th student to be admitted since the school’s reorganization in 1785. As she, and the 5,478 students before her, took their places in society, they carried with them the notion of school art as picturesque landscape drawings, pretty watercolor paintings, decorative craft projects, and perhaps a smattering of art history. This was a cultural expectation that would not soon be forgotten.

1. Haller, Mabel. Early Moravian Education in Pennsylvania.

Nazareth, Pa.: Moravian Historical Society, 1953, p. 316.

2. Ibid., p. 22.

3. Ibid., p. 240.

4. Haller. p. 254.

5. Reichel, William C. and William H. Bigler. Moravian Seminary

Souvenir. Bethlehem, Pa.: Bethlehem Female Seminary,

1901, p. 80.

6. Ibid., p. 141.

7. Ibid., p. 142.

8. Ibid., p. 67.

9. Ibid., pp. 68-70.

10. Ibid., p. 73.

11. Ibid., p. 78.

12. Ibid., p. 90.

13. Ibid., p. 155.

14. Haller, p. 244.

15. Reichel and Bigler, p. 156.

16. Ibid., p. 98.

17. “Needlework Accounts Box Number One”

18. Reichel and Bigler, p. 125.

19. Ibid., p. 27.

20. Margaretta Akerly, 1796, quoted in Swan, Susan Burrows. Plain and Fancy: American Women and their Needlework, 1700-1850. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977, p. 182.

21. Anita Schorsch, Mourning Becomes America: Mourning Art in the New Nation (Philadelphia: Pearl Pressman Liberty, 1967), p. 10.

22. Meyers, Richard, “19th Century Art and Artists,” Bethlehem Times, 28 December 1957.

23. “Rechnung 1808.”

24. “Rechnung 1811.”

25. “Day Book F: 1812-1818.”

26. Haller, p. 329.

27. “Ledger C, 1797-1813.”

28. Elizebeth Meyers, “Nature, History and Other Lore,” Bethlehem Times, 10/31/1929.

29. Reichel and Bigler, pp. 222-223.

30. Harriet Gould Drake Tinkam, “Recollections of Mrs. Harriet Gould Drake Tinkam,” mimeograph, p. 4.

31. Reichel and Bigler, pp. 222-223.

32. “Needlework Accounts Box Number One.”

33. Elizabeth Meyers, 1/28/1929.

34. Richard Meyers, 12/28/1957.

35. Elizebeth Meyers, 1/28/1929.

36. Reichel and Bigler, p. 233.

37. “1837 Memoranda, Rooms &c.”

38. “Class Lists 1836-1842.”

39. H. E. Brown, “Our Art and Artists,” Bethlehem Times, Sesqui-centennial Industrial Edition, June 1892.

40. “List of Evaluations. ca. 1859.”

41. Reichel and Bigler, p. 266.

42. Brown.

43. Elizabeth Meyers, 5/12/1927.

44. Brown.

©1990-2022 Roy Winkelman