Frederick Douglass: A Voice for Our Time

by Roy Winkelman

Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln by Frederick Douglass

- Lit2Go free audiobook recording (26 minutes)

- PDF of the speech (6 pages, reading level 11.1)

We live in an unhappy time of polarization, when many students (and perhaps their parents) don’t read news beyond the headlines and are quick to “cancel” someone for the wrong word used in a tweet from years ago.

It’s too easy just to categorize others and not consider the context of their former actions or words.

The Lit2Go recording of Frederick Douglass’ “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln” is a welcome antidote to that sort of lazy thinking. One of the intellectual giants of the 1800s, Douglass began life as a slave and worked tirelessly to abolish slavery for others once he gained his freedom. He wrote, preached, and made speeches as a leader of the abolitionist movement. He also was considered a friend by President Abraham Lincoln and was invited to the White House on various occasions.

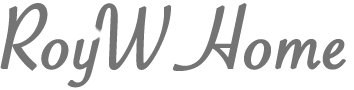

After the assassination of President Lincoln, freed former slaves raised funds to erect a monument to Lincoln. Frederick Douglass was invited to give a speech at the unveiling of the monument to an audience of some 25,000 people, including President Grant. Douglass knew first hand the injustices that his people had suffered. He also knew what Lincoln had done and had not done due to the necessities of the Civil War. He could have given a simple speech praising Lincoln as a perfect man and the Great Emancipator. Or he could have given a simple speech complaining of Lincoln’s faults in an attempt to “cancel” him. Either would have been an easy case to make. Instead, Douglass carefully laid out an insightful account of the times that Lincoln had found himself in. He gave praise where praise was due, but did not shy away from recounting the the issues upon which he and the late president had strongly disagreed.

Emancipation Memorial photo from Wikimedia Commons

The speech may be difficult for students who prefer to view everything in an either/or fashion, but that’s all the more reason to expose them to the careful thinking and distinctions that Douglass makes. The speech is a master class in nuance, fairness, and an appreciation of context that we can all learn from.

You and your class could spend a week researching and discussing this speech. Since you probably can’t devote that amount of time, I’ve added several historical sources that your students may not be aware of.

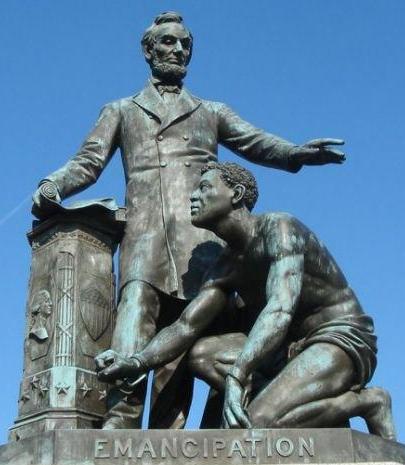

- The figure of the slave would have been a well-known emblem of the emancipation movement to most of the assembled audience. (See PDF below.) Re-using that pose, but with the chains broken was probably an intentional choice of the sculptor.

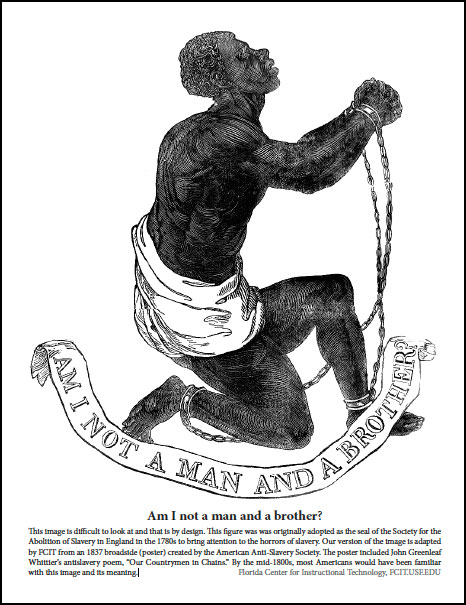

- Douglass certainly did not think the sculpture told the whole story, but rather than dismissing the Lincoln sculpture, he instead suggested an additional sculpture in a letter to the editor. (PDF below.)

Am I not a man and a brother?

This image is difficult to look at and that is by design. This figure was was originally adopted as the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery in England in the 1780s to bring attention to the horrors of slavery. Our version of the image is adapted by FCIT from an 1837 broadside (poster) created by the American Anti-Slavery Society. The poster included John Greenleaf Whittier’s antislavery poem, “Our Countrymen in Chains.” By the mid-1800s, most Americans would have been familiar with this image and its meaning. (309KB PDF)

Douglass' Letter to the Editor

Just a few days after delivering his famous oration at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park, Douglass wrote a letter to the editor of the National Republican calling for the addition of a second statue in the park, since no single monument “could be made to tell the whole truth of any subject.” Douglass reaffirms the credit due Lincoln and honors President Grant for his work, but then calls for a statue of a standing Black citizen as a complement to the Emancipation Memorial with its “couchant” Black man. (595KB PDF)

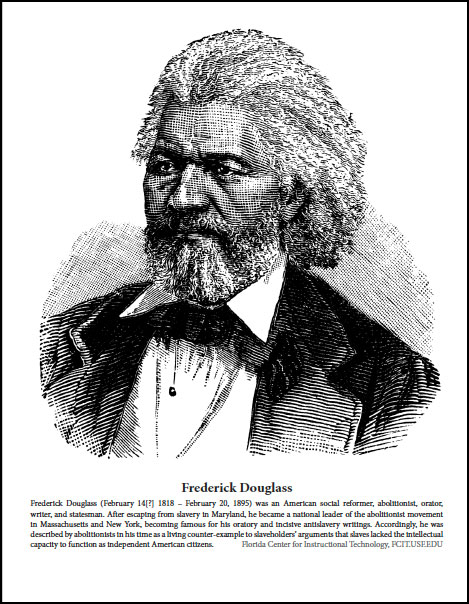

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (February 14[?] 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, becoming famous for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counter-example to slaveholders’ arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. (943KB PDF)